Using AI to harness the beautiful complexity in T-cell receptor diversity

Matching with The Mark Foundation for Cancer Research

Here we talk to MATCHMAKERS team lead Michael Birnbaum, of Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and Ryan Schoenfeld, CEO of The Mark Foundation for Cancer Research (co-funders of the MATCHMAKERS team) about how the T-cell receptors challenge really puts the “grand” in grand challenge. We discuss how the team is mapping interactions between major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-bound antigens and T-cell receptors on an unprecedented scale to develop computational tools to accurately predict, for the first time, unseen patient-specific tumour antigens recognised by different T-cell receptors, and expand the impact of immunotherapies for more cancers and more people.

Introducing team MATCHMAKERS

Earlier this year, Cancer Grand Challenges funded five new teams to work on four challenges. Representing a total of $125m over five years, this was the largest investment made by the initiative in a single funding round to date. Our international network of like-minded partners and donors made this possible.

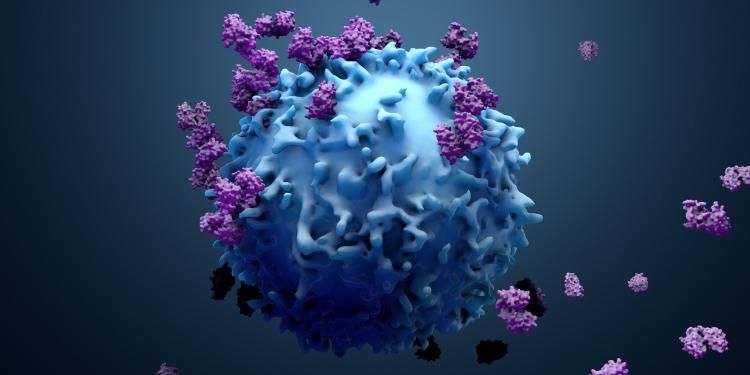

Team MATCHMAKERS are taking on the T-cell receptors challenge. Led by Dr Michael Birnbaum at MIT, this international team of researchers spans 12 labs, 10 institutions, and five countries and brings together world-leading immunologists, engineers, computer scientists and structural biologists as well as clinicians and patient advocates. By generating and integrating vast datasets, the MATCHMAKERS team plan to develop powerful new artificial intelligence (AI) tools that can predict T-cell receptor antigen specificity – paving the way toward the development of more effective and personalised immunotherapies.

The Mark Foundation for Cancer Research partnered with Cancer Research UK to fund this ambitious team through the Cancer Grand Challenges initiative, founded by Cancer Research UK and the National Cancer Institute in the US. This is the third time Cancer Research UK has joined forces with the The Mark Foundation to fund a Cancer Grand Challenges team, taking The Mark Foundation’s total investment in the initiative to $33m. The Mark Foundation’s CEO, Ryan Schoenfeld, reflects, ‘The time is right for this challenge. The promise of using the latest evolutions of AI to really push the envelope and make these predictions seemed like the perfect problem. And the impact could be huge, transcending cancer even.’

The MATCHMAKERS team’s proposal excited Ryan for two reasons. ‘They’re working with world class artificial intelligence leaders,’ he says, ‘and they have committed to generating bespoke data sets at the large scale required to drive AI-fueled insights.’

Training at scale

Since the release of the original AlphaFold and RoseTTAFold programs (the latter developed by MATCHMAKERS team member David Baker’s lab at the University of Washington) to predict protein structure, exciting progress has been made toward accurately predicting how proteins interact with each other and their ligands. These advances, or even things like ChatGPT, have shown that if you have enough training data, eventually it is possible to generalise and make predictions. Naturally there has already been a lot of interest in trying to use AI tools for immune recognition, given how immunotherapies have transformed how cancers are treated, but that biology is still catching up. As Michael reflects, ‘One of the amazing things is that we know that the T cells are able to recognise targets in the tumour, but more often than not we don't know what's recognised during the course of that response.’

But so far, it has not been simple to predict which antigens T cells will recognise. On attempts to predict specificity so far, Michael says, ‘They tend to be fairly good if you have a tonne of data for one target, but if you try to move even to a slightly different target then you just don't generalise at all. So the bet that the team is making is that this really is due to the fact that something like 70% of all current data is against 100 targets, and so if there are billions of possible targets, then the data is just nowhere near spread out enough to make any real play at generalised predictions.’

Michael emphasises, ‘It'd be the equivalent of trying to train a model where you want it to be able to tell you anything it could see, but you're only training it on pictures of cats and tennis balls.’

This is where the team’s approach comes in, generating data not just at scale but across a breadth of targets, both natural and synthetic, and integrating different classes of data, both sequence and structure. By massively expanding the amount and coverage of training data, the team hope to be able to generalise and develop tools that will allow accurate prediction.

As Ryan points out the scale of Cancer Grand Challenges funding is critical in making this work possible, ‘Without funding on this $25 million scale, you wouldn't be able to generate these large data sets that just don't exist at present.’

Pretty darn grand

Tumour antigens are patient specific, so the ability to predict unseen epitopes, those that the algorithms have never been trained with is critical. As Michael puts it, ‘That's what puts the grand in the grand challenge here.’ So, how will the team get to this point?

Michael details the team’s approach,

What we will be doing is judging the progress as we go along and changing our data collection strategies as we go in order to get there. We’ll be using stepping stone challenges along the way — relatively easier formulations to problems and then relatively more difficult formulations to problems, hopefully matching our capability as we ramp up the data.

The funding flexibility that the Cancer Grand Challenges approach provides will allow the team to adjust course as they move forward towards addressing the challenge. And Ryan hopes the Cancer Grand Challenges scientific committee can also help along the way, ‘Through the annual review process, the scientific committee provides unbiased insights and asks tough questions.’

An example of a smaller question that MATCHMAKERS plans to tackle first is whether, upon sequencing T-cell receptors and mutations in an individual patient’s tumour, can the team predict which receptors recognise which antigens. Michael reflects, ‘This itself is still pretty darn grand actually. Can we make good matches between the potentially dozens of T cells in the tumour and potentially hundreds of targets in the tumour? So the universe is not billions on billions. It's not true de novo prediction. It's still fairly complex but a much more constrained matching exercise.’

Another stepping stone challenge is whether the team can take T-cell receptors for known targets and tune up their activity, or fine-tune activity to abolish off-target effects, to convert receptors into versions that could be utilised for therapy. As Michael puts it, ‘Can we then computationally design them to improve their properties?’ This mini challenge should be easier than designing a receptor completely from scratch, but progress in this area alone could already have a massive impact for patients.

Michael reflects, ‘Our team really views the challenge of predicting what your own T cells recognise with their T-cell receptors and designing new T-cell receptors as linked. We think that if we're able to do one, we're going to be able to do the other.’

Added layers of complexity

As if the T-cell receptor challenge wasn’t grand enough, the concepts of tumour heterogeneity and tumour evolution add layers of complexity on top. Antigens presented by the tumour may vary depending on the region sampled, and antigens may evolve over time in order to escape immune recognition. As Michael puts it, ‘There's a tonne that we can do with just understanding the matches, but in terms of insight about what's happening in a person, it's still an incomplete picture. We also need to understand how often you would have to update what's being targeted, how often would you have to monitor it?’

Transforming prediction capabilities towards personalised immunotherapies

MATCHMAKERS’ ultimate goal is to transition the prediction of T-cell receptor antigen recognition from a highly specialised process that requires heroic experimental effort and is currently limited to a few laboratories worldwide into a routine clinical test available for all. This will transform the ability to develop personalised immunotherapies tailored to the unique characteristics of an individual’s cancer and T cell repertoire.

But by gaining a deeper understanding of T-cell receptor antigen interactions, MATCHMAKERS’ work will also have far-reaching implications beyond cancer to wherever antigen recognition plays a critical role, including infectious diseases, autoimmunity and allergies.

Ryan reflects, ‘Having Cancer Research UK, the National Cancer Institute and The Mark Foundation for Cancer Research all behind the team really keeps the focus on translational next steps that will emerge out of this project’s successes. The ultimate goal is identifying what will have the most impact for cancer patients.’

--------------------

Read more about team MATCHMAKERS and its approach.

Through Cancer Grand Challenges, The Mark Foundation for Cancer Research also fund teams SPECIFICANCER and NexTGen.