ecDNA: unfortunate accident or active player in glioblastoma development?

Team eDyNAmiC’s latest findings in glioblastoma, an aggressive, difficult to treat, brain cancer.

We talk to team eDyNAmiC future leader Chris Bailey, a clinical scientist based at University College London Hospital and the Francis Crick Institute, about his co-first author Nature paper, Origins and impact of extrachromosomal DNA, and how collaboration at this scale works. This paper is one of three papers published back-to-back by the team. We also discuss his hope that this resource cracks opens the field, allowing others to delve into the findings to further our knowledge of extrachromosomal DNA (ecDNA) and importantly inform more translational studies.

Medicine for me combined two things that I really liked doing- working with patients and understanding the underlying biology that causes disease. I opted to train in haematology, as it combined academic opportunities together with getting to know patients very well, as through the treatments you see patients regularly over a long period of time and get to be a part of their journey. Before my specialist training, I completed a masters in epidemiology and then went into bioinformatics and tumour evolution, becoming an “academic nomad” during the process.

Charlie Swanton’s and Mariam Jamal-Hanjani's labs are focused on tumour evolution, and ecDNA subverts our general understanding of tumour evolution. It's something that can be studied longitudinally and I was looking for a project that allowed me to develop skills in bioinformatics. ecDNA and focal copy number amplifications weren’t a strong focus in the original TRACERx papers, so I went to a conference and introduced myself to Paul Mischel, and that’s how I got into ecDNA! Cancer Grand Challenges set the ecDNA challenge and eDyNAmiC was conceived - a phenomenal collaboration between a variety of labs that were interested in the same thing. I was lucky enough to become a part of that. And so combined with the fact that I had just started working within the Genomics England environment, everything came together for this study.

We use whole genome sequencing data from the Genomics England 100,000 genomes project, to quantify the prevalence of ecDNA across 39 tumour types, from nearly 15,000 patients. Critically the data comes with good clinical annotation, such as survival statistics, treatment data and pathology reports.

So- It's not easy. This is the first answer! It was three hard years of data cleaning and then once you have the ecDNA calls, generated through the computational pipelines that have been designed and set up by myself with Vineet Bafna and Paul’s lab, you get to think about the analysis. That's the best bit because it's where you exercise your creativity, and think- what are the important questions that need to be answered?

It’s difficult but rewarding and has been made all the better because of the ethos of team eDyNAmiC. I see it as series of networks, the immediate network is the lab itself, where I'm able to get help and advice from the huge range of people, the post docs and PhD students, that work at the Crick Institute with Charlie and with Mariam. Then the wider network is eDyNAmiC.

One of the cool things about eDyNAmiC is the ease at which communication is facilitated, it's phenomenal.

We found that that ecDNA is particularly prevalent in sarcomas, in HER2+ breast cancer and in glioblastoma. That there are mutations present on ecDNA that are under positive selection, and that gene amplification and mutation are working synergistically to drive tumour evolution.

We know from previous work that ecDNA amplifies oncogenes, but we went on to find that a large proportion of ecDNA did not contain oncogenes at all. So we asked- what's the purpose of these genes- if it's not to amplify traditional oncogenes that drive growth and enhance survival? We found that these genes were enriched for immunomodulation and inflammation, and working with Nicky McGranahan’s lab, showed they were associated with reduced tumour T cell infiltration.

We also found ecDNA that didn't contain any genes at all. Taking previous data from Howard Chang’s lab, we were able to annotate promoter and enhancer sequences on these ecDNAs. We found incidences where ecDNA that contained oncogenes was co-amplified with ecDNA that didn't contain any genes at all.

Then with Serena Nik-Zanial, we were able to look at mutational signatures, and show that samples with ecDNA had higher tumour mutational burden. Oriol Pitch, co- first author of the paper, came up with a method to time mutations according to when ecDNA forms, so we could date when different kinds of mutational processes occur. This allowed us to look at the association between specific tumour suppressor gene mutations and the presence of ecDNA.

At the same time Vineet Bafna’s lab were working on the ecDNA computational tools, developing Amplicon suite, which allowed us to also look at the complexity of the ecDNA.

Finally, we were able to correlate ecDNA with poor survival, and not just because a tumour might be inherently genomically unstable. We could also show that treatment was linked to ecDNA presence, and perhaps associated with its formation as well.

The treatment association analysis was actually suggested by a reviewer, asking do you have treatment data? I didn't think we'd see anything because we thought the effect we saw was all driven by stage. But we also observed an association with treatment, so that was very unexpected.

One of the things that also got me was seeing that there were so many ecDNA that weren't oncogenic at all. The extent of that was surprising for me and something that we wanted to dig into.

I hope this work emphasises how prevalent and important ecDNA is in cancer biology, and leads to more awareness of it. Hopefully people now go away and ask how does the treatment association work? What are the specific treatments that might cause ecDNA to form and can we use that to further inform clinical practise? By making these observations now, I hope they will help inform trial strategies, targets, and which patients we might want to focus these strategies on.

The patient advocates are just such an amazing and essential part of what we do.

ecDNA is a concept I find quite difficult to explain to my relatives and friends, as well as its importance within the sphere of cancer research. The patient advocates have been able to facilitate that, which has helped me enormously as a communicator in trying to deliver those messages.

Within eDyNAmiC we’ve been able to have constant communication with the patient advocates, which has driven the research in a more translational direction, to be more patient focused- that has been crucial to the narrative of this study. And to the overall narrative of the work in eDyNAmiC.

eDyNAmiC has opened the door to working and collaborating with a vast network of people, all unified by a similar goal and it has facilitated new collaborations and new opportunities.

I've learned a lot from being a part of the Future Leaders programme, as well as from going to the Cancer Grand Challenges summit and observing the PIs that work within the Cancer Grand Challenges framework, how good leaders do things and what is required in this particular example for good leadership.

I've learned a bit about how you work with so many moving parts, in particular whole labs that are coming from various parts of the world. I've learnt that it is actually possible to collaborate with 150-200 people despite the despite the obvious difficulties. I think eDyNAmiC is an example of how that can be done in a, I wouldn't say completely unstressful, but friendly collegiate collaborative, communicative manner!

I've had two kids in the lead up to this paper (the oldest is now 3 and the youngest 8 months), so nights have been interesting! But having the kids has meant that I've been able to deal and rationalise all the other stresses that go on a bit better. We were on holiday as the acceptance letter came in, which was perfect. I think when the paper comes out, a glass of champagne in the kitchen with my partner will be enough.

Cheers Chris!

Chris has now gone back to the hospital, splitting his time between completing his haematology training programme and continuing with research. He hopes to obtain a clinician scientist fellowship that would put him on the track to independence, in order to explore ecDNA in the haematology sphere.

Learn more about the three papers published back-to-back by eDyNAmiC

------------------

Find out more about team eDyNAmiC. Through Cancer Grand Challenges team eDyNAmiC is funded by Cancer Research UK and the National Cancer Institute, with generous support to Cancer Research UK from Emerson Collective and The Kamini and Vindi Banga Family Trust.

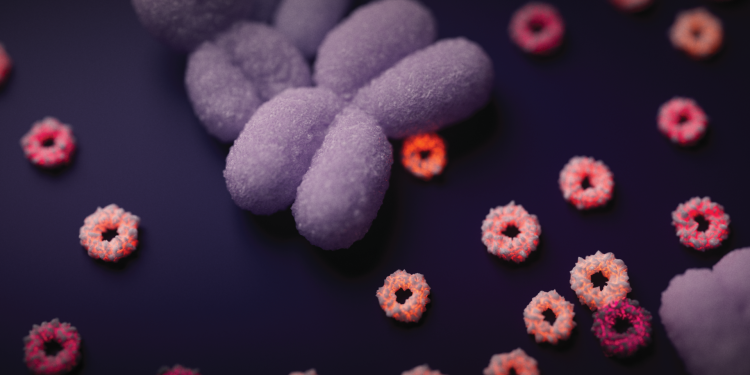

Hero image: Artistic visualisation of extrachromosomal DNA. The large, purple rod-shaped object is a chromosome. The smaller orange-red circles are the extrachromosomal DNA. Credit: Jeroen Claus

Team eDyNAmiC’s latest findings in glioblastoma, an aggressive, difficult to treat, brain cancer.

New findings from team eDyNAmiC

New tool published by team eDyNAmiC.